Article

How Do College Students Really Learn Best?

The goal of any educational endeavor is to help students acquire the desired skills and knowledge and to prepare them for what comes next. Learning, however, is not a static concept or simple process. Student experiences, learning environments, technology, cultural factors, and many other elements contribute to the quality and extent of student outcomes. Reading the recent Inside Higher Education (IHE) article “How College Students Say They Learn Best” (Flaherty, 2023) and the takeaways it presented caused me to reflect on how the topics of “what do students prefer” and “which method is best” related to one another…

Learning Preferences Is A Complicated Proposition

Learning is a multifaceted process that involves various cognitive, social, and emotional factors. Unfortunately, many college students do not fully understand how learning occurs most effectively or the critical factors and respective effort required. They likely have not been involved in a first-year experience program where The New Science of Learning book (Zakrajsek, 2022; recommended!) was incorporated as required reading. As a result, they may prefer the path of least resistance or that which is most familiar – the traditional lecture – and may not be able to proactively apply or advocate for the most effective learning strategies.

Why Some Students May Prefer Lecture Format

There are multiple reasons students may state preference for the lecture format or even believe that it is most effective for their learning:

- It is usually the format with which they are most recently familiar from secondary education.

- It is what they most likely will experience across a majority of their lower-division college courses.

- Familiarity with this format can breed a sense of comfort, security, and safety.

While these are certainly critical factors that contribute to motivation and self-actualization (Maslow, 1954), they are just the beginning in terms of learning potential. Without better understanding, how can students determine which mode of learning helps them the most?

Deep Learning Is Hard Work

Though students may state greater preference or benefits from passive lecture instruction, it is actually those involved in active instructional methods who benefit the most (Deslauriers et al, 2019). We know from a metaanalysis of 225 studies that active learning increases learning performance (Freeman, et al, 2014). Active learning offers many benefits, including:

- Active engagement through problem-solving, experimenting, discussing, creating, debating, debunking, etc.

- Deeper levels of thinking and action, which can take students out of their comfort zone

- Taking risks and navigating setbacks

- Making mistakes, often by design, as that is where the most effective learning can happen.

The problem is that the additional effort, struggle, and mistakes common in active learning environments “can be misinterpreted by students as a sign of poor learning” (Deslauriers et al, 2019). But, if it is made known to students that this is a natural and essential part of the process and they are enabled to have a growth mindset (Dweck, 2007), much deeper learning will occur.

Why It’s Not All Active Learning, All the Time

Since I haven’t already, I want to acknowledge that lectures are not all bad. There are times when it is a valid mode of instructional delivery or context experience for the student. It’s just that when used as the predominant default, lectures can lead to a content-centric approach that may not effectively enable significant engagement, agency, and ownership of the learning experience.

So why is the passive lecture-based instruction still so prevalent? Reasons include:

1. Passive lecture-based instruction can be a comfort zone for instructors as well as students.

Most faculty were primarily developed through their graduate school programs to be researchers and content experts. These are extremely intelligent professionals, yet too often they have not been given the critical knowledge or skill set to enable deep student learning. When preparing a delivery-focused lecture, instructors zero in on content and presentation, relying on textbooks and ancillary materials as well as increasingly vast amounts of content on the Internet.

2. Passive lecture-based instruction makes it easier to control what takes place in the session.

There is less class management required and less risk of the unexpected. Lecturing also doesn’t require the time and effort it can take to initially select, learn, prepare, and implement active learning techniques.

3. Students don’t always appreciate active learning styles.

Consider the risk/reward ratio when an instructor incorporates significant active learning. Active learning techniques may actually receive lower student evaluations of teaching effectiveness because students are not accustomed to the fact that struggle can be part of a successful learning experience. They instead may interpret it as a negative and give the instructor a lower rating.

This can be problematic, particularly for probationary faculty or contingent instructors up for review. The problem may be exacerbated when senior faculty and administrators who are making personnel decisions do not realize that active learning may result in greater learning (mission critical), yet lower evaluations of teaching effectiveness.

Striking A Balance On the Lecture-Active Learning Spectrum

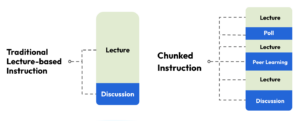

Doing what is best for student learning does not have to involve going all-in at either end of the lecture-active learning spectrum. We know from the Student Voice Pulse survey of 1,250 students that the majority of students report learning best when there is some level of active learning. Through intentional course design, learning sessions or modules can be anchored in a reasonable amount of content-focused delivery (e.g., passive lecture, recordings) interspersed with active learning opportunities more students desire. The graphic below provides a simple example of how a 50-minute passive lecture might be optimized by instead providing time and space for students to engage with each other in problem-solving, analyzing a case study, or otherwise collectively discussing topics and solutions within the lecture context.

Enabling Further Adoption of Active Learning

To support a greater shift toward interactive lectures, we must find ways to more effectively illuminate active learning effectiveness research when having conversations within our institutions and professional organizations. Here are some ways to facilitate those conversations:

Work to become collectively further informed and skilled at supporting and facilitating active and engaged student learning.

Invest in further support of the existing instructional workforce.

Advocate that graduate programs require or recommend their candidates to complete learning experiences related to principles of course design and development, effective and inclusive teaching strategies, and methods for assessment of learning and timely feedback.

As most faculty currently teach across multiple modalities to changing student demographics who will enter the rapidly evolving workforce, these efforts become increasingly critical.

How Alchemy Makes A Difference

At Alchemy, we help institutions and faculty create humanized, engaging and inclusive learning experiences. We enable faculty through providing curated resources and the personalized support they need, when they need it.

References

Deslauriers, L, McCarty, L. S., Miller, K., Callaghan, K., & Kestin, G. (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom, Applied Physical Sciences, 16, (39), 19251-19257.

Flaherty, C. (2023). How College Students Say They Learn Best. Inside Higher Ed. April 11.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H, & Wenderoth, M. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Psychological and Cognitive Sciences, 111, (23), 8410-8415.

Maslow, A (1954). Motivation and personality. New York, NY: Harper. ISBN 978-0-06-041987-5.

Zakrajsek, T. (2022). The New Science of Learning. Stylus Publishing.